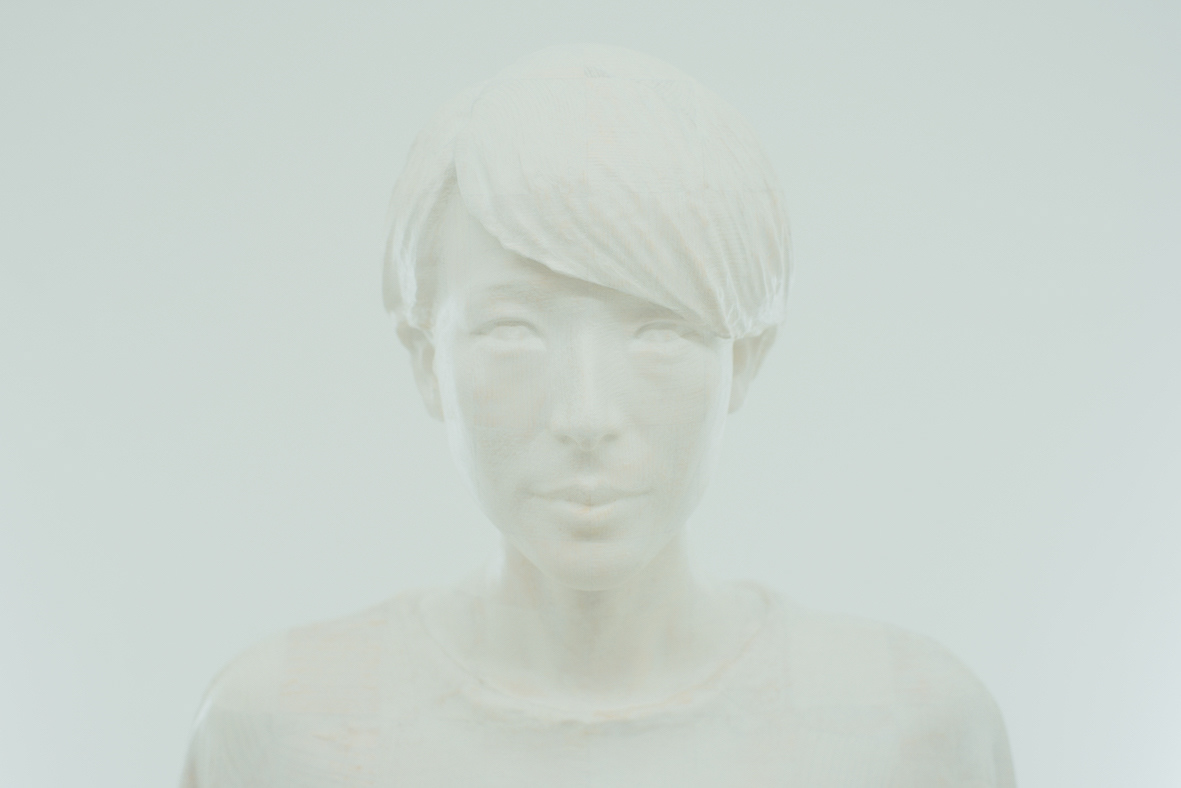

Misty

2019 152x42x25cm japanese cypress, oil stain

Misty -意識の境界-

ある人がある空間に立っていた。ある人が纏っている空気。その空気はどこから来ているのだろう。私が感じた空気はその人自身からなのか、それともその人が立っていた場からだったのか。場だとすると、その背景にあるモノたちや建物の中の空気だったのかもしれないし、モノたちも含め建物が建つ街や都市、その土地の風土以上の何かだったのかもしれない。仮にある人自身からのものだったとしても、それもまた、その人が過去に触れてきた空間やモノたちを感じているのかもしれない。そんなふうに空気を追っていると、人と空間の境界がどんどん薄れ、気づけば霧が立ち込める茫洋とした世界にいた。

ある人と空間の境界をスキャニングする。彼女が纏っている服は、人と空間を繋ぐモノであり、その姿から微かに残る重力と地平線の痕跡を手掛かりに、仮想空間の中で空気を探す。モニターから見える人の形は、重さも厚みもゼロであり、物質的な塊やマッスもなければ、重力も空間も感じない。感触がない私が見ている世界はただの光なのだ。でも私は「ない」感覚に近づいた。

凡ゆる人やモノは様々なモノとコトを受け入れ築かれているかのように、檜の正六面体を格子状に組んだ塊を、xyzの方向からプロッタで切削し、消えてしまった人の形を表出させる。そして離散的な塊と表面を再構築し、ある人が纏っていた空気の記憶を辿りながら彫刻する。

ある人の「ない」彫刻を、無機質な小さな空間に置く。蛍光灯の白い光に包まれ場の空気と交わる。そして空気を掴もうとしても掴めない感覚が白い壁の向こうまで広がっていく。

Misty -Consciousness Boundary-

A person stood in a certain space. The air that surrounds a person. Where does that air come from? Is the air I feel coming from the person themselves, or is it from the place where the person stood? If it's from the place, it might have been the air in the background or inside the buildings, or perhaps it was something more than the climate of the town, city, or land where the buildings stand. Even if it were from the person themselves, they might also be feeling the spaces and things they have encountered in the past. Following the air in this way, the boundary between people and spaces gradually blurs, and before you know it, you find yourself in a vast world shrouded in mist.

Scanning the boundary between a person and a space. The clothes she wears are things that connect people and spaces, and based on the faint traces of gravity and horizon remaining from her appearance, she searches for air in virtual space. The shape of a person visible on the monitor has zero weight and thickness, with no material mass or gravity felt. The world I, devoid of sensation, am observing is just light. But I'm getting closer to the sensation of "nothingness."

As if all people and things are built and accepted through various things and events, a mass of hewn cedar tetrahedrons is assembled in a lattice pattern, cut from the xyz directions by a plotter, revealing the form of a disappeared person. Then, while reconstructing the discrete mass and surface, sculpting is done while tracing the memory of the air that surrounded a person.

The "nonexistent" sculpture of a person is placed in a sterile small space. It intersects with the air of the room enveloped in the white light of fluorescent lamps. And the sensation of being unable to grasp the air spreads beyond the white walls.

Misty 2019.12,6 - 2020.1.25

void+ Tokyo

Photo:Kohei Yamamoto

Dissipating reality—Tomotaka Yasui’s female figures

Keisuke Mori

Curator, Chiba City Museum of Art

The distance of sculpture

The expression in the eyes of the female figures draws in the gazes of viewers in front of them. With their erect postures and eyes of glittering gemstones, an atmosphere of calm pervades these women. Made using the hollow dry lacquer technique, which involves applying layers of hemp cloth, and covered with delicate mother-of-pearl, Tomotaka Yasui’s sculptures are linked to time-honored traditional Japanese performing arts and have often been discussed in terms of their craft-like affinity with noh masks, Buddhist statues and dolls. Due to the softness of their forms and the restrained color of the white lacquer, they somehow evoke the warmth of the human body. And yet, due to their well-proportioned left-right symmetry, their frontality and their vague expressions, it is difficult to read their character or emotions. For several years, Yasui experimented with eschewing the use of real people as models. For this reason, it seems that his works are not necessarily devoted to visual reproducibility (though after the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, he reaffirmed the importance of standing face-to-face with actual people, and for his latest work, Misty, a real woman served as the model). Whether he is dealing with real or imaginary figures, the problem of reality that the artist confronts concerning the “existence” of human beings fills the work with ambiguity and uncertainty.

For Yasui, sculpture above all demonstrates the difficulty of giving form to one’s own senses. In thinking about this, what needs to be confirmed at the outset is that any study of humans is also directed at the subject in the form of the person doing the gazing. Yasui was born in Belgium, spent his childhood in Israel and eventually moved to Japan with his parents. One suspects this experience meant that, while he was able to assimilate various cultures and climates around the world, each time he moved he had to suspend having a fixed place for the purposes of understanding himself. Perhaps reflecting this special physical sense, Yasui’s female figures also convey the impression, despite the fact that they stand on their own with both legs firmly planted on the ground, that their very existence is continually shifting from place to place.

Grids—intersecting axes

The anguish of realizing as artworks the perceived world is probably demonstrated more clearly than anything else by the complex changes in Yasui’s methods to date. With chemically synthesized resin as his starting point, he has used various combinations of natural materials and techniques, including lacquer, mother-of-pearl, powdered brass and tin, while in his latest work he has experimented with woodcarving using a 3D plotter. In addition to poplar and Japanese cypress, he has also used acrylic cubes as a material, with constant modification continuing in recent years to address the gap between his senses and his forms. As if rejecting fixedness itself, the axes Yasui attaches importance to in order to regulate his constantly wavering self as well as his subjects are the horizontal and the vertical. Through the repeated intersection of these at regular intervals, he generates consecutive squares, or in other words grids. Variations on a range of grids can be detected in Yasui’s works, including the mother-of-pearl embellishments and cuboid forms that serve as the minimum units of his structures and the polygons and pixels invoked in his virtual spaces.

In recent years he has also experimented with expanding his sculptures further into space. An example is the project conducted in collaboration with an architect and a cabinetmaker in an abandoned house in Takamatsu, Kagawa, called Machi ni aru ie to iu chokoku (A house in a town as sculpture). Inside the building, Chokokuka no ie(Sculptor’s house), countless grids cover the floor and the furnished shelving. The space visualized here indicates a stable territory made up of the floor and wall surfaces that come into contact with the body and relates to the countless horizons and vertically towering rock faces and trees that humans have discovered in nature. Like we humans, Yasui’s female figures are also steeped in an uncertain existence in which they can only guarantee their own existence through the stability of such external environments.

Misty is a wood-carved work to which a thin coating of white paint has been applied based on its analogous relationship with the exhibition space. The title is also suggestive of a figure standing quietly in a misty place with poor visibility, reminding us of situations in which it is difficult to definitely objectify things. In creating the work, Yasui first 3D scanned a woman using specialist equipment before using software to revise at the data level such details as the hair and eyes. The various body parts were then carved out of Japanese cypress wood using a 3D plotter, and these were joined together and painted by the artist. Here, with the introduction of equipment such as the 3D scanner and 3D plotter, Yasui has in mind the complete removal of the artist’s own hands from the creative process. This was a new methodology for the purposes of better placing ambiguous “existence” between “presence” and “absence.” In this creative method, the automation of machinery using digital data becomes an important element of the work, but the clothing that covers the body as if to erase the individual characteristics of the model such as its chest, torso and hands assumes a particularly strong presence.

Clothing = interface

This is not the first time the artist has designed clothing so light it seems as if the model is enveloped in air. It would seem that this interest in clothing was influenced in no small way by Yasui’s mother, who was a textile pattern maker. For example, in the numerous fashion magazines such as Vogue that Yasui saw while growing up, it is the clothing that is imbued with both aesthetic and commercial value. This reversal of the relative positions of clothing and the model’s body would appear to correlate with the dilution of physicality and the foregrounding of the clothing seen in Yasui’s female figures. Here, however, we should probably pay attention to the fact that the clothes covering the models occupy the position closest to the artist’s physical senses. Yasui asserts that for humans, clothing itself is “the first layer of skin.” Hidden in the background of this assertion is a penetrating critical spirit with respect to the view of sculpture in Japan since modern times, which reflected on the origins of life in the depths of the human body and pursued the nude as the very ideal of sculpture.

Clothes, which are located on the outermost position with respect to the body inside in order to protect or adorn it, become a contact surface for the feelings and physical senses such as sight and touch directed at the object. Another term for this is an “interface.” Yasui’s sculptures truly take as their subject the artist, the figure in front of him and the entirety of the “misty” space the envelopes them both, with this surface as a boundary. Another artist who took up as a subject this orientation to the space surrounding the subject and attempted to sculpt the “distance” between the artist and their model was Alberto Giacometti. As the work of someone who does not rely solely on visual reproduction, Yasui’s sculptures come close to the small, slender figures of Giacometti, who tried to express the infinite distance between himself and his models, and deviated considerably from reproducibility. At the same time, there is a decisive difference that separates the two. They are both tactile and visual, but in contrast to the horizontality of the awareness Giacometti directs at the models sitting in front of him, Yasui’s sculptures demand an almost dermal perception that involves the entire surface of the body. But exactly what kind of subject is the mysterious “dissipating existence” that is generated through such perception?

The first clue to answering this can probably be found in the mother-of-pearl, gemstones and lacquer Yasui has used as materials in the past. While they make up the contours of the surface, the luster of the mother-of-pearl in which shells are elaborately shaped and the brilliance of the gemstones incorporate multi-directional and indeterminate qualities that, rather than establishing distinct boundaries, dissipate outwards. In the case of the lacquer, or the sap included in the hemp cloth, too, we should pay attention not only to the reflections of the glossy luster, but to the very chemical reaction related to molecules in the atmosphere during the process whereby it dries over a long period of time.

Surfaces as cave paintings

Isamu Wakabayashi is another sculptor who dealt with the relationship in which the self and the subject are separate yet connected in the space in which they exist. In his 1982 essay “Sakaigawa no hanran” (Flooding of the Sakai River), he wrote as follows about an event he experiences one day when it was raining.

Due to the rain, the surfaces alone of the people and buses I was looking at were emphasized. Moreover, these surfaces acquired density, rendering ambiguous the shapes of the people and buses. In addition to this, the sheets of rain falling between myself and these people and buses made me feel connected to them while rendering the subjects even more indistinct. (1)

In other words, due to the natural phenomenon of rain, Wakabayashi’s attention was drawn to the “ambiguous” surfaces of himself and his subjects, and he further discovered that in space filled completely with water drops, both were related to each other as a “connection.” The question of consciousness that Wakabayashi continued to pursue throughout his lifetime is in fact deeply rooted in his experiences of encountering Paleolithic cave paintings in Europe, and the vast deserts and remains of ancient civilizations in Egypt in the 1970s. The sensation of discovering surfaces of the earth that had accumulated time well in excess of a human life in the form of the traces of lines etched in wall paintings in caves or geological formations, and of being drawn to the “density” hidden behind his subjects, became an indispensable element in Wakabayashi’s subsequent practice. In the ambiguity of contours and of presence observable in Misty, I get a strong sense of an orientation to density that is of the same quality as Wakabayashi’s.

Under the conditions of contemporary society, in which our awareness of “the present” is unceasingly covered in excessive information, Yasui practices with his sculptural work a resistance to this time that passes at an increasing tempo and to this metamorphosing space. As part of this, he superimposes on the surfaces of his sculptures the density of time and space as the “depth” that was once perceived together with humidity and light in various places around the world. The world itself fills these thin surfaces and furthermore forms wide, deep, boundless presences. Perhaps the figures Yasui creates in his search for the depths of a perspective aimed at this overwhelming reality trigger in us a nostalgic feeling like a landscape we have seen somewhere before. However, for viewers to venture further than this is by no means an easy thing. Because, just as cave wall paintings and geological formations were for Wakabayashi, the surface characteristics of the clothes of the female figures at once assume the role of an interface while possessing qualities that anyone can read. At the very moment one tries to venture further into its depths, this surface can turn into a “barrier” to one’s senses. In the context of Yasui’s sincere and unceasing practice, these female figures that have been given form as “mist” stand quietly in the distance in an indistinct place that fills everlasting time and space.

1. Isamu Wakabayashi, “Sakaigawa no hanran” (Flooding of the Sakai River), I.W. Wakabayashi Isamu noto (I.W. Isamu Wakabayashi notes) (Tokyo: Shoshi Yamada, 2004), pp. 182–83.

霧散するリアリティ――保井智貴の女性像について

森啓輔

千葉市美術館学芸員

彫刻の遠さ

正面に立つ鑑賞者の視線を、遍く吸い込む女性像の眼差し。直立する姿勢とも相まって、輝く貴石の瞳を持つ彼女らは、静謐な雰囲気に満ちている。麻布による脱活乾漆の技法や、細やかな螺鈿が表面に施された保井智貴の彫刻は、日本古来の伝統芸能と結びつき、能面や仏像、人形との工芸的な類縁性が、これまでしばしば語られてきた。造形的な柔らかさや、白漆の抑制された色彩からは、人肌がもつ温かさをどこか感じさせる。だが、均整のとれた左右の対称性と正面性、茫漠とした表情から、個性や感情を読み取ることは難しい。保井は、実在する人物をモデルに用いない制作方法を、過去に数年間試みている。このことから、作品は必ずしも視覚的な再現性に委ねられていないようだ(とはいえ、東日本大震災を機に、人物と対峙することの意義を再確認し、最新作《Misty》にはモデルとなる女性がいる)。実在する人物であれ、架空の人物であれ、人間という存在に対して作家が向けるリアリティの問題は、曖昧さと不確かさを作品に充溢させている。

保井にとっての彫刻、それは何より自身の感覚をかたちとすることの困難さを示すものだ。このことを考えるにあたり、まず確認しておくべきは、人間への探求は、翻ってそれを眼差す主体である作家本人にも、向けられるということだ。保井はベルギーで生まれ、その後、幼少期にはイスラエル、やがて日本へと家族とともに生活の場が移り変わってきた。それは、世界の文化と風土の多元的な吸収でありながらも、自己を認識するための定められた場所を持つことの中断を、そのつど余儀なくされた経験ではなかったか。この特別な身体感覚を育んだ保井の女性像もまた、両足をしっかりと揃え、自立しているにも関わらず、存在自体は彷徨い続けている印象を受ける。

グリッド

格子――直交する基軸

感受された世界を、作品として実体化することの苦悩は、これまでの手法の複雑な変遷が、何より証明しているだろう。化学的な合成樹脂を出発点とし、漆や螺鈿、洋金粉や錫粉などの自然素材と技法の複合的使用がなされ、最新作では3Dプロッタによる木彫が試みられた。ポプラや檜以外にも、アクリルキューブが素材とされ、感覚と造形のズレに対する間断ない修正が、近年も続けられている。その定まること自体を拒絶しているかのような保井が、常に揺れ動く自身、さらに対象を規定するために、重視する基軸こそが、水平と垂直である。それらは、等間隔の直交を繰り返すことで、連続した方形、つまり「格子」を生み出す。螺鈿の装飾や、構造の最小単位となるキューブ状の形態、あるいは仮想空間で援用されるポリゴンやピクセルなど、様々な格子の変奏が、保井の作品には認めることができる。

近年ではさらに、彫刻をより空間に拡張する試みも行われた。建築家と家具職人と共同でなされた、香川県高松市の空き家での「まちにある家という彫刻」と呼ばれるプロジェクトである。この建造物《彫刻家の家》では、無数の格子が床や設えられた棚を覆っている。ここで可視化された空間とは、身体に接触する床と壁面による安定した領域を示し、それは人間が自然の中で無数に見出してきた地平線や、垂直にそびえ立つ岩壁や樹木とつながるものだ。そのような外部環境の安定によってしか、自己の存在を担保できない不確かな存在であることに、私たち人間と同様、保井の女性像もまた貫かれている。

《Misty》は、展示空間との相似的な関係から、全身が白一色に薄く彩色されている木彫の作品だ。作品タイトルからも、霧がかった視界のあやふやな場所に、ひっそりと佇む人物を思わせ、確固とした対象化が困難な状況を、私たちに連想させる。本作においては、まず専用の器具で女性を3Dスキャンし、その後ソフトウェアが駆使され、データ上での髪の毛や目といった細部の補正がなされる。そして、3Dプロッタが檜の角材に割り当てられた身体の各部位を彫り出し、それらを作家が接合、塗装していくという過程を経ている。ここで保井は、3Dスキャンと3Dプロッタという機器の導入によって、作家自身の手の介入の限りない消去を目論んでいる。それは曖昧な存在を、より「有ること」と「無いこと」の間に立たせるために、新たに試みられた方法論だ。この制作方法においては、デジタルデータを用いた機器の自動化が、作品の重要な要素となるわけだが、モデルの胸部や胴部、手といった個の特徴を抹消するように身体を覆う衣服が、ひときわ強い存在感を帯びている。

衣服=インターフェース

モデルの空気を纏うような柔らかな着衣は、これまでも作家によってデザインされてきた。この衣服への関心は、テキスタイルのパタンナーであった母親の影響も少なくないようだ。例えば、日常生活で保井が目にしていた『VOGUE』などの数々のファッション誌では、衣装こそが美的かつ商品的価値を帯びている。衣服とモデルの身体のそのような主客の転倒は、保井の人物像にみられる身体性の希薄さと、衣服が前景化することと相関関係にあるように思われる。しかしここでは、作家の身体感覚に一番近い場所に、モデルを覆う衣服があることに注目するべきだろう。保井は衣服こそが、人間における「第一の皮膚」であると主張する。生命の根源を身体の深奥に見つめ、裸体像をこそ彫刻の理想とし追求してきた、近代以降の日本での彫刻観に対する透徹した批判精神が、この主張には見え隠れする。

内側にある身体を保護、あるいは装飾するため、その最も外部に位置付けられた衣服とは、対象へと向けられた意識や、視覚、触覚といった身体感覚にとっての接触面となる。それは、「インターフェース」と呼べるものだ。保井の彫刻は、まさにその面を境界として、作家とその先の人物、さらに両者を包括する「霧がかった」空間全てを対象としている。そのような空間を含む対象への志向性を問題とし、作者とモデルを隔てる「距離」の造形化に挑んだ作家に、アルベルト・ジャコメッティがいる。モデルとの限りない遠さを表現しようとし、再現性を大きく逸脱した彼の小さく、細長い人物像に、視覚的な再現にのみ依拠しない保井の彫刻は、近接している。一方で、両者を分かつ、決定的な差異もある。それはともに視触覚的であれ、ジャコメッティが目の前に座るモデルに向けた意識の水平性に対し、皮膚的とも呼べる全方位的な身体での認識が、保井の彫刻には要請されている点だ。このような認識を通じて生み出される、謎めいた「霧散する存在」とは、果たしてどのような対象だろうか。

過去に保井が用いてきた螺鈿や貴石、あるいは漆といった素材に、その第一の手がかりは認められるだろう。貝殻を細密に造形化した螺鈿の光彩や、貴石の輝き、それは表面の輪郭でありながら、明確な境界を成立させるというよりも、むしろ外部へと拡散していく多方向で不確定な性質を含んでいた。麻布に含む樹液である漆も、艶やかな光沢の反射のみならず、長時間かけて進む硬化の過程で、空気中の分子と結びつく化学反応にこそ、目を向けるべきだ。

表面、洞窟壁画として

若林奮もまた、自己と対象が実在する空間で隔たれ、結び付けられる関係を主題とし続けた彫刻家だ。1982年の「境川の氾濫」という文中で、若林はある雨の日に体験した出来事を、次のように記している。

自分が眺める人間やバスは、雨によってその物の表面のみ強調することになった。しかも、その表面は厚みを持って、人間やバスの形をあいまいなものにしたのであった。それに加えて自分と人間やバスの間の無数の雨は眺める対象をさらに不明瞭にしながら、自分とのつながりを持たせるものとしてそこにあった。(註)

雨という自然現象によって、自己と対象それぞれの「あいまいな」表面を注視し、さらに隈なく水滴が満たす空間上で、両者が「つながり」として関係付けられていた事実を発見した若林。彼が生涯にわたり、探求し続けた意識の問題は、実のところ1970年代にヨーロッパで旧石器時代の洞窟壁画、そしてエジプトでの広大な砂漠や古代文明に触れた経験が、深く根ざしている。洞窟壁画に刻まれた線描の痕跡、あるいは地層として、人間の生を遥かに超える時間を堆積させた地表を発見し、対象の背後に潜む「奥行き」へ惹かれていった感覚は、以後の若林の制作にとって、必要不可欠な要素となった。この奥行きとは、別の言葉に置き換えるならば、時間と空間の「厚み」といえるだろうか。《Misty》において見られた、輪郭と存在の曖昧さには、この若林と同質の厚みへの志向性が強く感じられる。

「現在」への認識が、過剰な情報に止めどなく覆われていく現代社会の状況において、保井はその加速度的に流れ去る時間と、変容する空間への抵抗を、彫刻の制作において実践する。その時、かつて世界のさまざまな場所で、湿度や光を伴って感得した「奥行き」としての時間と空間の厚みを、保井は彫刻の表面に重ね合わせていく。世界そのものがその薄い表面を満たし、さらに広く、深く、茫洋な存在をかたちづくること。この圧倒的なリアリティに向けられたパースペクティブの深淵さを求める保井の人物像は、いつかどこかで見た風景のような懐かしい感覚を、私たちに生起させるかもしれない。しかし、さらにその先へ鑑賞者が踏み込むことは、決して容易ではない。なぜなら、その女性像の衣服の表面性とは、若林にとっての洞窟壁画であり、地層であったように、インターフェースの役割を担いつつも、誰もが読み取れる性質を持ち合わせていないからだ。深淵のさらに奥に踏み入れようとするまさにその時、感覚に対しての表面は、「障壁」ともなりうるだろう。誠実かつ飽くなき実践の中、「霧」としてのかたちを与えられたその女性像は、悠久の時間と空間を湛える朧げな場所において遠く、静かに佇んでいる。

註

若林奮「境川の氾濫」『I.W 若林奮ノート』書肆山田、2004年、pp.182−183